3 SLAC Scientists Receive DOE 'Early Career' Grants

Three SLAC scientists will receive Early Career Research Program grants from the U.S. Department of Energy for research to boost the peak power of X-ray laser pulses, model catalytic chemical reactions and build better simulations of particle collisions at CERN's Large Hadron Collider.

By Glenn Roberts Jr. and Lori Ann White

Three SLAC scientists will receive Early Career Research Program grants from the U.S. Department of Energy for research to boost the peak power of X-ray laser pulses, model catalytic chemical reactions and build better simulations of particle collisions at CERN's Large Hadron Collider.

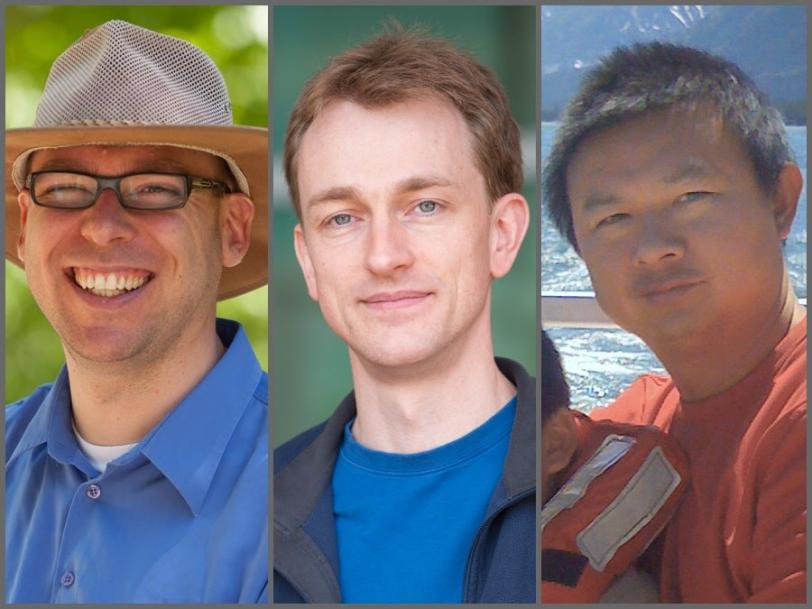

SLAC's Thomas Bligaard, Stefan Hoeche and Juhao Wu were among 61 scientists selected from a pool of 770 applicants for the five-year grants, which were announced last week by the DOE Office of Science. Seventeen of the grants are going to researchers at DOE laboratories, who will receive about $500,000 per year for salary and research expenses.

The grants support the development of individual research programs of scientists who received their doctoral degrees up to 10 years earlier. Recipients must be full-time DOE national laboratory employees or tenure-track assistant or associate professors at a U.S. academic institution, and their research topics must fall within one of six Office of Science focus areas.

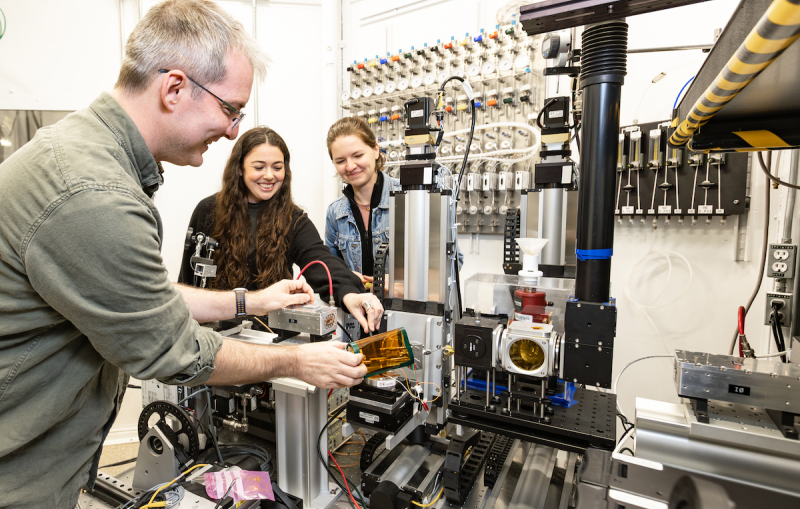

Thomas Bligaard

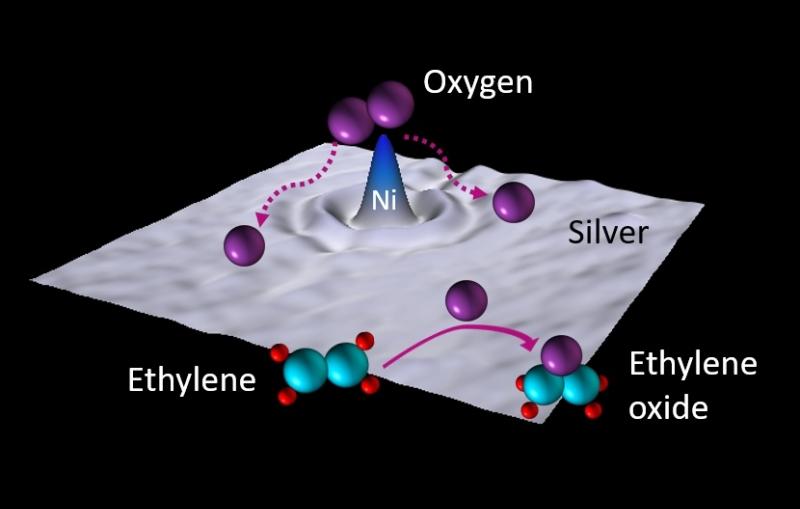

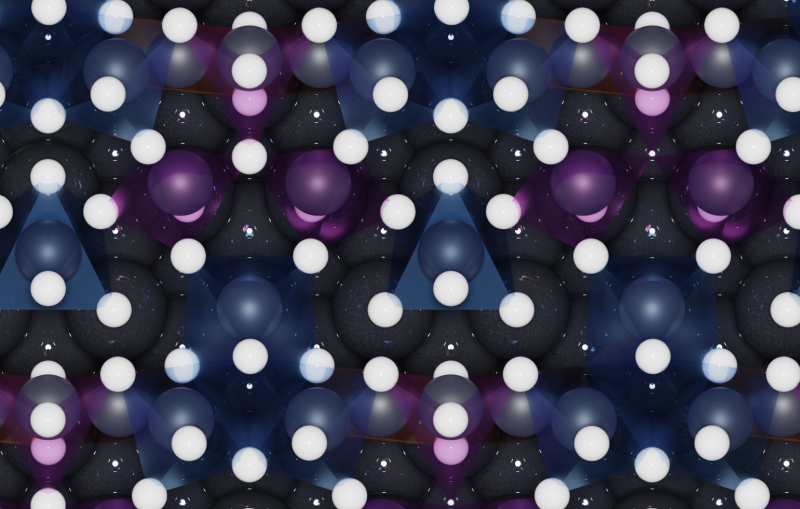

Thomas Bligaard, a senior staff scientist who joined SLAC's SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis two years ago, works to improve computer modeling of chemical reactions involving catalysts. Catalysts speed up reactions without themselves being consumed in the process. They are essential for many industrial processes, including the large-scale production of fuels and other chemicals, and for reducing airborne pollutants.

The grant will be useful in constructing more sophisticated, comprehensive codes that encompass a broader range of variables in chemical reactions and better represent complex materials, he said.

"There is a huge need for novel catalysts based on Earth-abundant materials that are cheap. All the simple things have already been tested over the past 100 years," Bligaard said. "To come up with something new, something better, we need to look at more complex materials, more complex surfaces. To do so, it's very beneficial to use computer simulations to evaluate thousands – tens of thousands – of catalytic surfaces simultaneously."

He added, "Computer simulations give us a very good idea of what will not work, and allow us to more carefully pinpoint which materials could be interesting to look at."

Some popular models tend to oversimplify chemical reactions by focusing on a particular molecule, he noted, rather than accounting for the entire chemical "soup," including how different chemical components, in a variety of concentrations, interact with a catalyst's surface. Bligaard said his group's improved models will address, "How do they react with one another? What is the state of the catalyst during this reaction?"

Research is expanding on materials such as sulfides, oxides and carbides, in particular, he said, and the modeling work of his research team will benefit the "Catalyst Genome," an effort to more fully map out the properties of catalysts.

"Thomas has taken on a project most of us in the field of catalysis have shied away from because it is extremely difficult: To develop a theoretical description of surface reactivity taking into account, in a consistent way, the interactions between the atoms and molecules at the surface," said Jens K. Nørskov, SUNCAT director. "This will pave the way for substantially better accuracy in predictive models of catalysis."

Stefan Hoeche

Stefan Hoeche, a member of SLAC's Particle Physics Theory Group, is also working on better simulations, but of a very different sort. He and his group are developing more precise simulations for researchers at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

"We're providing a tool that bridges the gap between theory and experiment," Hoeche said.

The theory in this case is Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), which seeks to explain the behavior of the quarks that make up particles such as protons and neutrons, and the gluons that keep them together. QCD theory is extremely complex and not fully developed, but since the particles slamming together at the LHC are protons, the rules laid out by QCD govern what ultimately appears in the detectors of experiments such as ATLAS and CMS.

The tool Hoeche's group is working on will provide improved QCD simulations to help the experimenters at the LHC recognize significant results that might currently be going unnoticed. Especially, said Hoeche, results that would indicate physics beyond the Standard Model, the current best explanation of the world of subatomic particles.

"This is a very important area, but understaffed," he added. "There are only three groups in the world currently working on this." He wants to use the funding to add another researcher and purchase computer equipment – the calculations needed to create the simulations are very computer-intensive. "The last calculation I did took about 300,000 CPU hours," Hoeche said.

Hoeche said he's excited that the DOE also recognizes the importance of his work, "but I'm also thrilled to be able to contribute to the LHC adventure."

Colleague Lance Dixon expressed confidence in Hoeche. "Stefan is one of the world's experts in understanding the complex collisions between two high-energy protons at the LHC," Dixon said. "He's leading the introduction of high-performance computing to this area of particle theory. I'm delighted that Stefan's talents have been recognized through this prestigious award."

Juhao Wu

Juhao Wu, a staff scientist in the Accelerator Research Division who joined SLAC in 2002, is studying methods to increase the peak power of pulses at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) by more efficiently transforming its electron energy into X-rays. The LCLS is an X-ray free-electron laser, or XFEL, and its ultrabright, ultrashort X-ray laser pulses are generated when an electron beam from the lab's linear accelerator traverses a sequence of alternating magnets in devices called undulators.

The goal of Wu's work is to achieve a peak power of 1 terawatt, or 1 trillion watts, in pulses about 10 femtoseconds long at LCLS and its planned expansion, LCLS-II. Such ultrashort pulses would improve the imaging resolution for a range of experiments, and could produce images of nanocrystals and single molecules in the instant before the X-ray pulse destroys them. A peak power of 1 terawatt is 30 to 40 times higher than presently possible at LCLS.

A technique known as iSASE (for "improved Self Amplified Spontaneous Emission"), and further development of another X-ray laser enhancement known as "self-seeding" are leading candidates to reach this terawatt goal.

Among the critical tools needed for the terawatt project are advanced diagnostics to measure the beam properties, Wu said.

"We need to understand the free-electron laser beam – both the X-ray light and the electron beam – on a deeper level," he said. "This can lead us to the final goal."

He added, "This is leading-edge research. This is really a critical step to demonstrate for LCLS-II. I'm really happy that the Department of Energy recognizes the importance of this research."

Wu is working with X-ray free-electron laser pioneer Claudio Pellegrini on the terawatt effort. SLAC's Agostino Marinelli and a few others have been contributing to the iSASE research, while self-seeding has been a major research and development focus at SLAC. The grant will support modeling and simulations, as well as the design, construction and testing of prototypes.

"This is very important research to develop the capability of X-ray free-electron lasers for high-resolution imaging of nanosystems and even smaller structures," Pelligrini said. "It is also important to keep LCLS at the forefront of scientific research in view of the increased competition coming from the new generation of XFELs, like SACLA in Japan, the European XFEL, and Korean and Swiss XFELs."